The Abalone Mother Lode and the Ghosts on the Seventeenth Green

Only sea otters and the local Indians considered the abalone worth eating before the 1850s. With both of those populations diminished, and neither Spaniards, Mexicans or Californios considering them edible, the abalone flourished and California's rockier coastline was soon covered with the tough-muscled mollusks.

For the Chinese immigrants to the Golden Mountain, the abalone was not only edible, but was a valuable and transportable commodity when dried. As the Chinese became painfully aware that they were unwelcome in the California gold fields, some came out to the coast to find their alternative Gold Mountain. In 1853, on the Monterey Peninsula, they discovered the Abalone Mother Lode. Soon groups of Chinese hunted though the coastal rocks during low tides, gathering the abalone and processing and drying them in their shoreside camps and shipping them in one hundred bound bales to San Francisco and ultimately to China.

The Shells Awaited a Market

Old sampans and abalone shells, Pescadero, Monterey County, c. 1880.

The Rumsien Indians, the original residents of the Monterey Peninsula, had always found abalone shells to be valuable, not only making implements and jewelry from them, but also trading them with Indians all along the North American coast. Known as "Monterey Shells" the large, pearlescent shells were a regular part of the fur trade in the Pacific Northwest.

The Chinese abalone companies arrayed around the Monterey Peninsula did not dispose of the shells. They stashed them in piles awaiting the shell brokers who would occasionally come along the coast, purchasing the shells for jewelry, buttons and furniture.

Jung San Choy comes to Pescadero

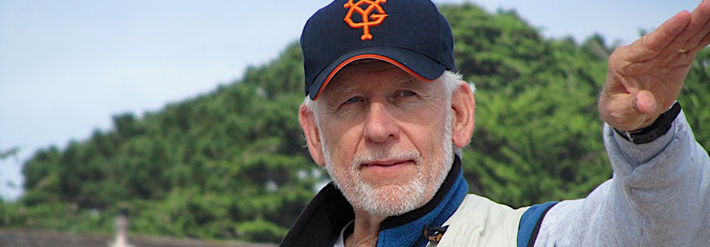

Jung San Choy, the Shell Seller of Pescadero.

In 1868, a 16 year-old Hong Kong-born Chinese named Jung San Choy arrived in California and eventually came to work and live in the Chinese fishing and abalone village known as Pescadero. (Jung was his family name, and we will use his name in traditional Chinese name-order, family name first.) The village of Pescadero went back to the 1850s, and the Chinese living there had always faithfully paid rent to whoever was their landlord. In 1870, Jung married another China-born immigrant, Yeung So, and they settled into a house overlooking present-day Stillwater Cove where they lived for the next half-century. All thirteen of their children were born in that family home, and all were United States citizens by birth.

The Seventeen-Mile Drive and Opportunity – 1881

The Pacific Improvement Company, the real estate branch of the Southern Pacific Railroad, purchased much of the western portion of the Monterey Peninsula in 1880, including the land the Chinese village occupied. It was the beginning of a physical and cultural transformation of the Old Capitol. Simultaneously, the PI Company built the grand Hotel Del Monte and brought a Chinese road grading crew in to build the Seventeen-Mile Drive through their new property (named the Del Monte Forest) as an excursion route for their hotel guests. Almost instantaneously, the Chinese fishing villages at Point Alones and Pescadero became "sights" on the new drive, affording upper-class visitors a chance to see the "exotic" Chinese communities. Every day, horse-drawn carriages drove past two villages that might as well have been plopped down directly from China. The original route of the Seventeen-Mile Drive took visitors right through the Pescadero Chinese village and within feet of Jung San Choy's house.

Jung children and shell stand along the Seventeen-Mile Drive near present-day Pescadero Point. Looking east, with Stillwater Cove in the background.

Jung San Choy realized that an opportunity was parading past his house every day, and he set up a small stand where he offered sea shells, trinkets and those "stored" abalone shells (cleaned up and polished) to the well-heeled passing parade.

Jung San Choy and Yeung So's family continued to grow during the 1880s and 1890s, with the thirteen and last child, (known to the family as 'Baby Bert) being born in 1904, when Yeung So was fifty years old. By the 1890s, Jung San Choy had three souvenir stands along the drive, and the Jung children provided much of the labor, stringing the urchin shells, polishing the abalone shells as well as staffing the stands. Jung's small souvenir stand empire was one of the earliest direct-marketing souvenir operations in Monterey.

Jung San Choy's value to the PI Company is apparent in that they only charged him a rent of fifty cents a month for his homesite, garden and barn. The Jungs were valued and respected tenants of the PI Company, and were well-known to the greater Monterey community.

Change Comes and the Jung Family Departs

Jung San Choy, left, and two of his older children at the shell stand near the family home along the Seventeen-Mile Drive.

In 1907, with his health declining, Jung San Choy visited China for the first (and last) time since originally immigrating to the United States. The trip and the immigration ordeal he had to endure both upon leaving and returning to the country took its toll on his health. The medical inspection he had to pass upon re-entering the U.S. noted that his health was so poor that he probably would not be able to conduct his abalone shell business any longer.

Meanwhile, in 1908 the PI Company began subdividing the land along the Seventeen-Mile Drive, selling the building sites to wealthy San Franciscans. Some of the building lots sold for thousands of dollars. The days of fifty cents a month leases for Jung and his fellow Chinese at Pescadero were over, and while the company built the Pebble Beach Lodge just to the west of the old Chinese village, the Jungs began moving to the San Francisco Bay Area. By the time Jung San Choy died of stomach cancer at age 67 in May of 1917, his children and widow were living all across the Bay Area. Later that same year, the first Pebble Beach Lodge burned to the ground.

The first round of golf was played on the new Pebble Beach Golf Links in 1919, and the memories of the Chinese village and the souvenir stands quickly faded away.

The Jungs Return, 1987

Jung family reunion, October, 1987. "Baby Bert" Jung in front row middle. Beach club is white building behind, located exactly on the site of the Jung ancestral home.

Seventy years after Jung San Choy's death five generations of his descendants had a reunion at the Beach Club, exactly on the site of their ancestor's home. Baby Bert, the last of the Jung children born at Pescadero was there, and he remembered his father telling him that he had planted those stately cypress trees that now frame the club's parking lot.

Each time I visit Pebble Beach and Stillwater Cove I try and listen to the late afternoon wind as it sighs softly through those cypress trees overhead. And if I stand real still, I can hear the sounds of Cantonese and the laughter of the thirteen Jung children born here above Stillwater Cove.

The Chinese Return, 2015

The economic balance across the Pacific has shifted dramatically since the nineteenth century. Now in 2015, Chinese immigrants and investors are coming across the same ocean that bore Jung San Choy over a century and a half ago. Busses filled with prospective purchasers trundle along the Seventeen-Mile Drive and the Chinese passengers ooh and ah at the famous golf course, perhaps unaware of the secret Chinese history that hovers there. Little do they know that over 150 years ago this very place was settled by fellow Chinese who also sought their fortune in the Gold Mountain and found it in the abalone on the rocks beneath the sundown sea.

A Note About Sources: You can find a more developed version of the Jung San Choy story in my book, Chinese Gold: The Chinese in the Monterey Bay Region, second edition, 2008, pp. 138-149; 544-546. The Jung family descendants have also been very helpful, including Mr. and Mrs. William Gee.