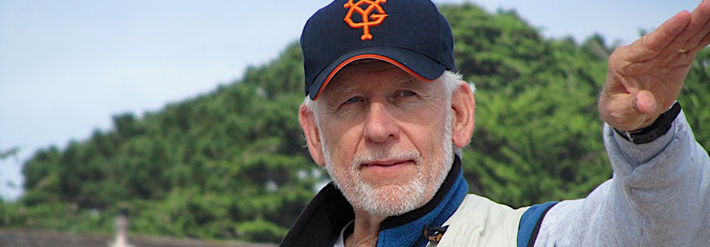

Chinese bonepickers moving through the Chinese cemetery in Colma, outside San Francisco. This process came to almost every Chinese cemetery in California.

The Bone Pickers:

Appeasing the Hungry Ghosts

A group of young boys ran into Watsonville that morning shouting, "They're digging up dead bodies in the cemetery! We saw skulls and everything!" It was a cold, February day, 1913, and this unusual scene was being reenacted just as it had a decade earlier in the cemetery north of town. A group of men quietly digging up the graves.

Small groups of townsfolk hurried out and gathered at the edge of the graveyard to watch, their hands over their mouths, as the Chinese men, armed with shovels quietly exhumed dozens of their countrymen. The onlookers gasped as they caught a glimpse of a femur or a skull, as the men cleaned the bones and carefully put each set in a box, preparing the remains for their last long journey home.

These were the bone pickers, employed by the Chinese Associations in San Francisco to fulfill the last element of a spiritual insurance policy made decades before when these men originally arrived in America. The deal was that, (in exchange for a fee) should the Chinese immigrant die here alone, the Association would see to it that he would eventually be reunited with his family back in China. Only then would his bones be in their rightful place on the altar in the ancestral hall and his spirit receive the honor and respect that his family could provide.

This was about more than just spiritual discomfort. Spirits of those who died beyond the ceremonial care of their family were consigned to the depths of hell, becoming hungry ghosts, the purveyors of mischief and bad luck. To reunite those Chinese who died in distant lands with their families was important not only for each of them, but also for the greater community.

The Graves

The Chinese buried in the Watsonville Chinese cemetery and others throughout the region were interred in the simplest of pine coffins. No need to invest in a fancy coffin if it was eventually going to be dug up and cast aside. The grave markers were white-washed boards with the deceased's name, home district and village and date of death painted on them. It would take about a decade for the flesh to dissolve and the remains to become transportable. In the meantime, the Chinese script on the grave marker often faded, or the marker itself rotted away or was burned in a fire, or vandalized.

The Chinese planned for the grave marker to be destroyed. In each coffin they placed a simple brick with the name of the deceased carved into it along with the village and district written alongside as a more permanent means of identification. The bone pickers usually moved through the older section of the Chinese cemetery with long metal spikes, probing for unmarked graves. Then, once found and exhumed, they used the burial brick to match the information in the association's records.

The Bones

The bone pickers worked like archaeologists, carefully removing the larger bones from the by-then rotted coffin and painstakingly washing and polishing them. It was important to find each and every bone, no matter how small, and as they sifted through the earth, they extracted the tiniest bones with long chopstick-like tools, placing each in the box made specifically for each individual body.

Once the bones were identified and placed in the box, the deceased's name, district and village were written on the lid of the box and shipped to San Francisco where they were assembled in larger shipments bound for China.

In February 1913, it took two weeks for the bone pickers to remove 68 sets of bones from the Watsonville cemetery. Those boxes joined an astonishing flow of similar boxes – estimated at 10,000 for 1913 alone – headed back across the Pacific.

The bone pickers usually tossed the burial bricks aside, and over the years they were informally recycled by scavengers and found their way into brick structures through the region. Some were buried in the undergrowth to be found during later cemetery renovations. In 1974, the brick in the accompanying photograph was found at Santa Cruz's Chinese cemetery at Evergreen by a group of my students who had volunteered to remove some of the undergrowth from the very overgrown graveyard.

The Bone Picker's Legacy

Non-Chinese watched these exhumations with revulsion and horror. And, as they often did with Chinese cultural practices they didn't understand, they expressed their revulsion by passing legislation to prevent it. The State of California, during its most virulent anti-Chinese paroxysm in the late 1870s, passed a law entitled "An Act to Protect Public Health from Infection Caused by Exhumation and Removal of the Remains of Deceased Persons." After 1878 it was necessary for the bone pickers to approach local public health officials to get a permit before they could exhume the bones. Ironically, this permit requirement makes it somewhat easier for modern-day historians to reconstruct just how many sets of remains were removed from some of the regional cemeteries.

A Haunted Landscape

We'll never really know how many deceased Chinese are still in local and regional Chinese cemeteries. As gravemarkers disappeared and Chinese communities waned and the older bachelors passed away, there were few active local Chinese associations to keep records or care for the cemeteries. The practice of boxes of bones returning to China stopped in 1949 when the Chinese government stopped receiving the shipments, marooning forever on this side of the Pacific, countless Chinese spirits, forever condemned to be hungry ghosts.

Beyond the cemeteries there are probably many Chinese remains buried in long-lost impromptu graves alongside railroad tracks, near tunnels, or beneath long-forgotten landslides.

[Note: Many of the stories about the mass-murder of Chinese miners are NOT true, including one of the most persistent about the coal mine near Malpaso Creek. I will address that rumor in a future article. Watch this space.]

One such isolated burial was uncovered in the sand at Sunset State Beach in 1957, and through a set of fortuitous circumstances, the remains received a proper burial in April, 2008. [We'll tell that story in a future edition.]

Feeding the Hungry Ghosts

According to Chinese tradition, all of the ghosts are released from heaven and hell during what is known as Ghost Month (late August-September on the lunar calendar) and are free to roam in the realm of the living. During this time, each family pays tribute to not only its own ancestors, but also, more generally to those ghosts that died without the benefit of family. It's all about respect, really. The spirits of those who did not receive the required respect will continue to cause mischief and mayhem until they do.

It is my belief that there was never a more marginalized and disrespected group in the Monterey Bay Region than the Chinese. The Chinese hover on the far edges of Santa Cruz's history and imagination. Santa Cruz was the home to the most virulent anti-Chinese organization in nineteenth-century California; mass meetings were held on the Lower Plaza and mobs chanted "The Chinese Must Go." Yet, despite the hatred and violence directed toward them, the Chinese persevered, carving out niches in agriculture, fishing, and domestic service, contributing to the town's economy and history.

However, they never received the respect that they deserved. Or deserve. Then, or now. Most of them died alone in this toxic and hostile landscape, their life stories dying with them.

We can only imagine the number of hungry ghosts wandering the regional landscape.

It's not too late to appease those spirits and to give them the respect and recognition that they never received in life, nor later in death.

Collectively we can be that family that they left behind in China. It's never too late to celebrate their contributions and their lives.