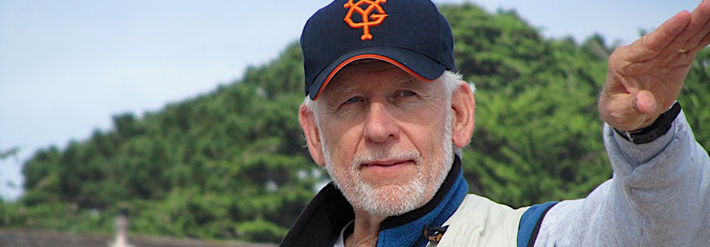

The northern or Wright's end of the Summit Tunnel and one of the Chinese laborers that helped build it, c. 1890.

The Myth of the Railroad Tunnels and the Japanese Invasion, 1942

There are a number of myths that have their origins in the early weeks of World War II following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The myths that have persisted include Japanese sailors coming ashore in Capitola armed with shotguns and a Japanese submarine hidden in a cave on the coast north of Davenport. And, perhaps the most pervasive one is that the Southern Pacific Railroad blew up their trans-Santa Cruz Mountain tunnels to prevent a Japanese invasion.

Myths grow from small seeds of truth watered and fertilized by hysteria and fear. There were Japanese submarines operating along the California coast in late 1941, and in one instance, the submarine I-23 surfaced off the coast on December 20 and chased an oil tanker into

The Wright's end of the Summit Tunnel, 1973. The photograph was taken while standing on the rubble created by the Army's explosions in 1942.

Monterey Bay as local residents watched in horror. The tanker was damaged, but escaped. The image of that submarine stayed in the local consciousness for many years, fueling stories of invasions and submarines hidden in caves. Neither the US military or Japanese military records support those stories. (See my book, The Japanese in the Monterey Bay Region, pp. 99 ff. for a more complete account of the December 20, 1941 submarine incident; see also Silent Siege III, by Bert Webber. Webber has done the most extensive work on the Japanese naval attacks on the coastline of the United States.)

One event that got woven into this Japanese invasion business was the destruction of the Southern Pacific Railroad's two long tunnels in the Santa Cruz Mountains in early April of 1942. Constructed almost entirely by Chinese railroad workers between 1876 and 1880, the tunnels had served as the primary railroad connection between Santa Cruz and San Jose for sixty years. Declining rail traffic and the severe winter storms of early 1940 brought the over-the-mountain railroad to an end and the last train through the mountain ran on February 26, 1940.

For the next two years the tunnels sat, open and abandoned. The Southern Pacific Railroad became increasingly concerned about the potential liability should the tunnels collapse, so in the early months of World War II they invited the US Army to practice their demolition work and collapse the ends of the tunnels. This they did on April 4, 1942. The explosions were heard throughout Santa Cruz County and were serious enough to be recorded on a seismograph at Santa Clara University.

The Wright's end of the Summit Tunnel, 1973. The US Army collapsed this end of the tunnel on April 4, 1942.

In the public's mind, the collapsing of the tunnel mouths was somehow connected with the continuing concerns about a Japanese invasion, and the myth developed that the tunnels were destroyed to prevent their use by invading Japanese. It wasn't so, but the myth does reflect the very real fear that residents of the Pacific Coast felt during the early years of the war.

Submarines off the coast? Yes. Tunnels blown up? Yes. Connected? No.

And the local folks looked up and asked, "Who was that dude who came and set our historic record straight?"

It was the History Dude!

Hi Yo Hooey! Awaaaaay.