This is the only surviving photograph of the Chinese fishing camp located from the early 1850s to the 1880s at the base of the bluff on present-day New Brighton State Beach. Photo credit: UCSC Special Collections

Why is New Brighton State Beach not called China Beach?

The Chinese Fishermen in the Monterey Bay Region

By now you are probably familiar with the contributions that immigrants from China made during California's Gold Rush and the construction of the Trans-Continental railroad, but you may not know about their pioneering efforts in California's fishing industry.

Coming from a country whose fishing resources had been heavily used for thousands of years, the Chinese quickly recognized the enormous potential for fishing on California's long, relatively untouched coastline. Beginning in the 1850s, they established fishing camps on coves and beaches and began harvesting the water's bounty. Most of the fish they caught were dried and shipped to markets along the coast and across the Pacific, while Chinese fish peddlers sold their product fresh in local towns. During the 1850s and 1860s, the Chinese had the fishing business pretty much to themselves, but beginning in the 1870s,as non-Chinese fishermen entered the region, they were forced to less-desirable out of the way locations.

The largest fishing village in the Monterey Bay Region was this one located at Point Alones in Pacific Grove, California. The initial focus of these fishermen was abalone, but they later shifted to drying rockfish and finally in the 1890s, squid. The village survived for so long because it was located mid-way between Pacific Grove and Monterey in a relatively isolated cove. The village existed from 1854 to 1907.

The cove just east of present-day Capitola's Depot Hill was a perfect location for the Chinese to develop and maintain their fishing operation. Tucked in at the base of the bluff, the Chinese village was not only out of sight, but also away from competition with other fishermen. The Chinese fishermen obtained their fresh water from springs that came out of the bluff, and they were able to exist in that legal limbo between high tide and the beginning of private property. There may have been a formal arrangement between the adjacent landowner and the Chinese, but we have yet to find a lease or agreement.

One contemporary eyewitness who left us a description of the village was Santa Cruz newspaper reporter Ernest Otto. The houses were about six feet above ground and the bluffs were picturesque with its growth, especially when the evening yellow primroses were in bloom. The boats were usually beached in front of the village and gave it a real touch of China as they were pointed at each end with a graceful curve.

Sampans pulled up on the beach at the Point Alones village,Monterey.

Photo Credit: Pat Hathaway Collection, Monterey.

The boats with the "graceful curve" that the Chinese used all around Monterey Bay were the traditional Chinese sampans. Made locally by the Chinese using traditional boat building techniques, the boats often attracted the attention of non-Chinese because of their unusually arched shape. One Monterey newspaper described the boats as "odd-shaped and lumber some-looking [boats] that float over the billows, when lightly loaded, with both ends in the air." The boats were as seaworthy as thousands of years of development in China could make them, however, and the locals soon came to respect sampans as being eminently practical on Monterey Bay.

The fishing technique used by the Chinese in the bay waters adjacent to their village was different than that used on the rocky shore off Monterey. At Monterey the Chinese used hook and line fishing primarily because the bottom was too rocky to allow the dragging of a seine. At China Beach, however, they used nets with one end attached to a pole stuck in the beach, and then using the sampan, they would swing the other end out beyond the surf line and bring it back farther up the beach creating a U-shape. The bottom of the net was weighted, while the top had floats attached to it, creating a wall of net from which the encircled fish could not escape. Then, using a windlass to assist in pulling in the fish-filled net, the Chinese dragged their prey up onto the beach. Most of the fish were split, salted and dried in the sun.

Chinese fish peddler on Santa Cruz Railroad wharf, c.1880s. The baskets in this photograph are empty and nested together. When full, the two baskets were suspended from the ends of the carrying pole that he is carrying over his shoulder.

Photo Credit: UCSC Special Collections.

The End of the Village

The village at China Beach seems to have lasted into the mid-1880s. But the Chinese fishermen were never secure or comfortable enough at this location to bring their wives and family members. In contrast, for example, the village over in Monterey was secure enough, and many Chinese children were born there, giving continuity to that story. Even today, there are descendants of the Monterey Chinese fishing village living in the neighborhoods above the old village site.

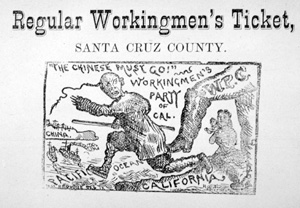

At China Beach, however, there is no such continuity. The pressures of the virulent anti-Chinese movement in Santa Cruz County, the effects of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and the legislation directed at the Chinese fishing techniques along the Santa Cruz County coast eventually spelled the end of the village. We don't know when they finally left, but by 1900, the waves and tides had done their work and the village was no more.

Later Fishermen at China Beach

The broad sand beach and smooth ocean bottom offshore continued to be attractive to fishermen in the twentieth century. Using techniques similar to those pioneered by the Chinese before them, a number of small-scale commercial fishermen continued to fish from the shore.

Dried fish destined for the Chinese markets in California and across the Pacific. Note the hat for size reference, and note the size of the mesh of the net.

Photo Credit: National Archives, Washington,D.C.

The development of local tourism and the coming of the name New Brighton.

Meanwhile, beginning in the late 1870s, China Beach was flanked by two resort developments. On the west was Camp Capitola, a vigorous and sizable planned development owned by Frederick A. Hihn. The completion of a rail link to Capitola with the coming of the Santa Cruz Railroad in 1876 began a small real estate boom just around the bluff from China Beach.

A smaller resort development began in 1877 on property owned by Thomas Fallon just east of China Beach. Fallon, an Irish immigrant and ex-mayor of San Jose (1859-1863), named his campground Camp San Jose to attract tourists from his hometown. The name did not attract the number and quality of tourists (they were often called "San Jose hoodlums" in the local press) that Fallon had hoped for, so in 1882 he changed the name of the camp ground to New Brighton. The New Brighton campground never enjoyed the success of that of nearby Capitola, however, and when Fallon died in 1885, the ownership shifted to his descendants who periodically leased the property to campground managers. The name New Brighton remained, however, both on the road that served the campground and the railroad stop above.

The anti-Chinese image from the top of a Santa Cruz County ballot, 1879. The anti-Chinese movement was extremely strong in Santa Cruz County in the 1870s and 1880s.

Credit: Santa Cruz City Museum

China Beach is renamed New Brighton.

In 1933 the state of California purchased the property where China Beach had been located and the land immediately north of it for a state park. The property remained without a name for several years, but finally the Director of State Parks decided to name the site New Brighton. John Sinclair, one of Thomas Fallon's descendants, objected vigorously to the state "taking" the name, but his protest was not successful, and the park officially was named New Brighton State Beach.

As years passed the name China Beach receded further and further out of local memory. The waves of time erased the name. Only now and then, after a winter's storm, did Chinese pottery pieces emerge from the sand to remind of the Chinese fishermen who had lived and worked there.

Fishermen pulling boat on rollers up China Beach,1913. This remarkable photograph was taken looking west, with present-day Park Avenue in the distance on the left, and New Brighton State Beach on the right. The box used to ship the fish is on the beach just to the right of the horse. The fish were probably shipped by train from the local railroad stop nearby. Credit: Sutton Family Collection.

E Clampus Vitus Revives the Name

In 1984, the story of China Beach caught the attention of the historical (and often hysterical!) organization known as E Clampus Vitus. They purchased a plaque (with wording written by the History Dude) and installed it in one of those only-the-Clampers-do-things-this-way events on October 20, 1984. This was the first permanent commemorative marker honoring the Chinese to be erected in the Monterey Bay Region.

The Pacific Migrations Visitor Center – 2003

Change came to New Brighton State Beach when the park was completely renovated in 2003. Through a unique collaboration between the California Department of Parks and Recreation, the Friends of Santa Cruz State Parks, and a team of historians and fund raisers, we have brought the Chinese story to the fore once again.

This photograph shows the same angle as the one the left 90 years later. Note that the bluff on the right is now covered with vegetation. The trees in the distance are the same as or descendants of those showing in the earlier photograph. Most are eucalyptus. Note that the beach is much narrower now.

In an imaginative exhibit that integrates the human migrations with those of birds, fish, mammals and butterflies, we stuffed an incredibly diverse number of stories into the small building. Inside the exhibit rooms you can see and smell (!) the stories of the Ohlone, Chinese, Californios, Irish, and Italians as well as those of the visitors who have been coming to this coast from California's great interior valleys.

Come visit the Visitor Center!

Before or after your obligatory visit to the beach, take the time to walk over to the Visitor Center. There you will learn to see and hear all of those who have gone before, and who knows, you might pick up a piece of pottery that the Chinese fishermen brought here over a century ago.