Japan’s Fire Balloons:

The World First Intercontinental Missiles, 1944-45

World War II brought many cross-over innovations to America’s military arsenal including the super-secret plan named “Project X-Ray” that involved strapping tiny incendiary bombs to bats and dropping them over Japan. This combination of zoology and weapon technology was intended to set fire to Japan’s mostly wooden cities and towns. These bat bombs never made it into combat and were eclipsed by another secret and much more destructive plan known as the “Manhattan Project.”

Meanwhile the Japanese were working their own reservoir of ingenuity with a secret project named Fu-Goto use the high-altitude atmospheric conveyor belt to deliver incendiary bombs to the west coast of North America and spread fire and panic among the Canadian and American populations. And maybe boost the morale of the Japanese population that was still feeling the shame of the April 1942 air raid led by Lt. Colonel James Doolittle.

“Weather Dude Time-Out:

America’s first recorded encounter with the Western Pacific winter jet stream came in November 1944 when a B-29 pilot reported encountering 175 mile per hour headwinds 30,000 feet over Tokyo. At first Army Air Corps meteorologists didn’t believe him but subsequent pilot reports prevailed. Those winds were one of the reasons that General Curtis LeMay changed bombing tactics in early 1945 and had the B-29s drop down and fly their bombing runs at night at 2,500 feet. ”

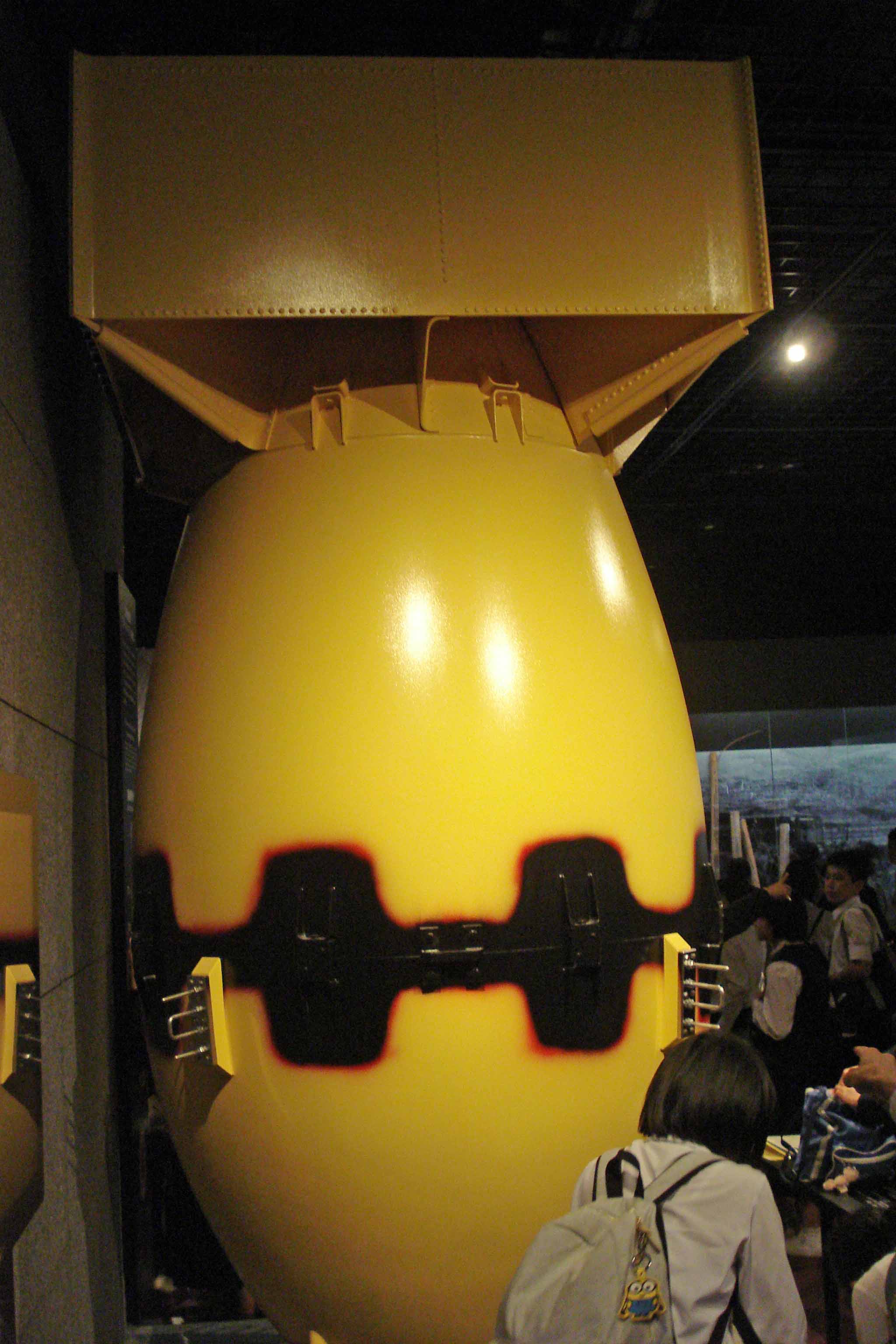

Schematic of the Japanese fire balloon. The entire outfit measured 100 feet from the top of the balloon to the bottom of the gondola.

The Technical Challenge

After experimenting with silk and rubber balloons the Japanese scientists determined that the balloons would be filled with hydrogen and made of paper. Using their centuries of traditional paper-crafting, they designed a balloon made of laminated sheets of paper made from pulped bark of the mulberry tree.

This was no backyard project – factories were set up to make the hydrogen, and huge unused buildings were filled with teenage girls who painstakingly glued the paper into sheet that would become the balloons. All done in total secrecy as the girls didn’t know what the balloons were being used for – “weather balloons?” –and remote Pacific Coast beaches beneath the jet stream were selected as the secret launch sites.

To carry the 300 pound payload of equipment, incendiary bombs, and ballast sandbags, required a balloon 32 feet in diameter. The payload swung 70 feet below the monster balloon. The entire thing was 100 feet from top of balloon to the bottom of the circular-shaped contraption. The non-Japanese who saw them said they resembled chandeliers. They may have looked like a contraption put together for a school science project, with their exposed wires and sandbags and small bombs, but they could be (and were) deadly.

Some of the wires and sandbags were part of the system that kept the balloons flying above 30,000 feet and in the jet stream. By venting hydrogen when the balloon heated up and flew too high, and dropping sandbags when it cooled and flew too low, the balloons bobbed in long graceful curves high above the Pacific. Few Japanese or Americans ever saw them in full flight in the upper atmosphere, but they probably looked like giant sea creatures – jellyfish – as they leaned eastward, the payload trailing behind.

The balloon were designed to fly for three days and nights, and then, no matter where it was, a timer would begin venting hydrogen descent, it would drop its payload of bombs, and then self destruct..

Unguided Intercontinental Missiles

Downed fire balloon found outside the town of Grimes, California in the Sacramento Valley west of Yuba City. It was found on March 14, 1945, and you can get a feeling for the size of the balloons – gondola is hanging in air to the right. Several ballast sandbags and bombs were intact.

the plan was to send up a huge paper balloons filled with ever-volatile hydrogen (remember the Hindenburg?) and hope that the balloons traveled at least 4,000 miles. And then they would drop incendiary bombs into the cities or forests of western North America and set them on fire. Unguided Intercontinental Missiles. (The working definition of an intercontinental missile is one that can travel a minimum of 3,400 miles. I’m not sure who decides such things but that’s the definition.)

Weather Dude Here. The unavoidable flaw.

You’ve probably already figured out the major flaw in this – even if the balloons made it across the Pacific and then dropped the incendiaries into the woods. It’s WINTERTIME in the woods. Snow. Rain. Wet wood. Drippy pine needles. No dry grass

The Japanese knew that the seasons were off and the odds were terrible, but by 1944 they were desperate as reflected in the kamikaze campaign that began in October 1944. up against it. They calculated that even an estimated 10% success rate would make it all worthwhile.

Each balloon cost the equivalent of $2,000 in 1945 US dollars, and the Japanese military ordered 10,000 of them. $20 million! By the time that the first balloons were launched in early November 1943 food shortages were common throughout Japan. The schoolgirls making the balloons were sneaking and eating globs of the paste as they glued the paper squares together.

The Final Flaw

One more really important thing: they were lobbing them over the horizon and they had no way of knowing whether they landed, set something on fire, came down in the ocean. They were depending on word of the balloons and bombs being reported by American or Canadian eyewitnesses, newspaper and radio reporters, and the news of the bomb balloons getting back to Japan. They were counting on Americans and Canadians being their spotters.

The Japanese didn’t know that the arrival of the balloons would become top secret in North America just as they were in Japan.

This map shows the general track of the balloons and the locations of the 350 balloons that survived. It was not until after the war that the Japanese who participated in the campaign knew that any of the balloons had reached North America.

The West Coast Mystery

The balloons began arriving in North America within a week. Initially their purpose was a mystery to the Western Defense Command. The markings indicated that they were of Japanese manufacture but to what purpose? As their number grew from solitary to several dozen, the military thought they might actually be carrying biological agents. Testing proved that not to be the case, but the persistent question continued to be their origin. Where were they coming from?

The possibility that the balloons were coming from Japan was initially discounted. Remember, the idea of the jet stream was not yet common knowledge in the United States. The theories ranged from off-shore Japanese submarines, German prisoner of war camps to Japanese concentration camps.

Clamping a lid of secrecy.

Uncertain about any of it, but concerned about starting a wave of panic on the West Coast (one of Japan’s intentions), the Western Defense Command established a news black-out about the balloons. Newspapers and radio were forbidden to report on the balloons, and citizens who found them were not to touch them, and contact local law enforcement.

But that same lid of secrecy also meant that when the military found out that the balloons carried potentially deadly explosives, they could not inform the public of the potential danger posed by the balloons and their strange cargos.

Tragedy in Oregon

Later historians of the story of the balloon bombs have suggested that the tragedy that occurred on May5, 1945 near Bly, Oregon might have been avoided had the general public been warned. But, as it happened, some children on a church picnic found one of the unexploded gondolas hanging in a tree and before the day was over, 4 children and two adults from what is now known as the Mitchell incident, were dead. These six American civilians are counted as the only wartime deaths on the continental United States due to enemy fire.

Geology to the Rescue

Several of the gondola payload came to earth with some sandbags still intact, and the US Geological Service had a unit in the Army that began to try and determine the origin of the sand used as ballast. By a process of elimination, they concluded that, indeed, the origin of the sand was Ichinomiya, a beach on the western coast of the Boso Peninsula in Central Japan. Eventually the geologists named two additional beaches as the source of the sandbag fill.

The Manhattan Project near miss

On March 10, 1945 one of the balloon bomb gondolas was trailing across the Eastern Washing? Landscape when the support lines tangled in a forest of high voltage power lines setting off explosions all through the grid, and causing a major power interruption. Some of the power in that grid was going to a top-secret governmental facility named the Hanford Engineer Wprks. That project was processing uranium into plutonium to be used in the nuclear bombs scheduled for testing in the New Mexico desert and possible use on Japan. The interruption caused by the balloon forced them to shut down the facility for over an hour and interrupted the production of plutonium for about a week. The plutonium made at the Hanford facility was used to make the bomb known as “Fat Man” that was dropped on Nagasaki in August 9, 1945.

“Fat Man” – Life-size model of the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, August 9, 1945. The plutonium for this bomb was made in a nuclear reactor at the Hanfor Engineering Works, Washington.

Tokyo is burning

At the same time that the balloon bomb interrupted the work of the Hanford facility – on the same day – the United States Army Air Force under General LeMay’s direction, sent 334 B-29s over Tokyo. They dropped 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs on the city, burning down nearly half of the city and killing upwards of 100,000 people. That raid still stands as the most destructive air raid in history, even beyond the two atomic bombs.

From out here in the 21st century, Japan’s balloon bombs look almost comical beside the roar of over 300 B-29s setting fire to half of Tokyo. But, we should not make the mistake of dismissing the Japanese balloon bomb campaign. The intention of the balloon bombs sent by the Japanese was the same as General LeMay’s – to set fire to their respective targets and spread panic, despair and death among the citizenry.

With the Japanese homeland now on fire and still not knowing if any of the balloons had landed in North America, the leaders of the balloon bomb campaign decided to terminate the project. They sent the last balloons in April, 1945.

The Balloon Bomb story today

Blinded by the glare of the fire-bombing that continue into the late summer and the flash of the two atomic bombs, the story of the balloon bombs remained a footnote in Japan’s wartime history. Even now, there has been little published about the campaign on either side of the Pacific.

In the end, the Fu-Go operation was a failure. No major forest fires were set, and the few small ones were extinguished by the winter storms that were fellow-passengers on the jet stream,

The most developed balloon bomb exhibit is in the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum which devotes a large space to a reduced-scale balloon and gondola. That exhibit is adjacent to several others devoted to the history of Tokyo during World War II, including a huge wall map showing the extent of the devastation of the March9-10, 1945 firebombing, including a film of the B-29s flying over the city, with full audio. The sounds of the bombers fill the room as they filled the city that night. The juxtaposition of the Japanese balloons that rode like sea creatures elegantly and silently across the Pacific against the rumble of the B-29s is sobering.

For Further Reading:

Coen, Ross. Fu-Go: The Curious History of Japan’s Balloon Bomb Attack on America. University of Nebraska Press, 2014. This is the most current treatment of the subject and contains a fascinating analysis that the role that racism played on both sides of the Paacific.

Mikesh, Robert, Japan’s World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on Northern America. The Smithsonian. A comprehensive analysis of the subject published as a paper in the Smithsonian’s Annals of Flight series, Number 9, 1973. This paper can be found on line, and it is filled with some of the best photographs of the balloons.

Webber, Bert. Silent Siege III: Japan Attacks on North America, Webber Publishing Group, Oregon, 1997. Webber was a consummate researcher on the subject of Japan’s various attacks on the Pacific Coast during World War II, including submarines and balloons. His books can be maddening as they are sometimes collections of disparate writings. During his lifetime he arranged a number of reunions between participants from the United States and Japan. He died in 2006, but Silent Siege is still available through Amazon and worth the effort to work through it.